Download the 2016 Survey Report

The history of Libertyville’s Downtown survey area reflects the arc of both commercial and residential development at the core of what is now the Village of Libertyville, and includes historic resources from that span from the mid-19th century to the present day. First settled in the 1830s, the village grew at a slow but steady pace through the 19th century, then experienced a boom in the early 20th century, when improved transportation to and from Chicago enticed city businessmen to purchased country estates around the village. While it struggled through the decades after World War II, today Libertyville’s downtown is thriving, as is the residential are surrounding it.

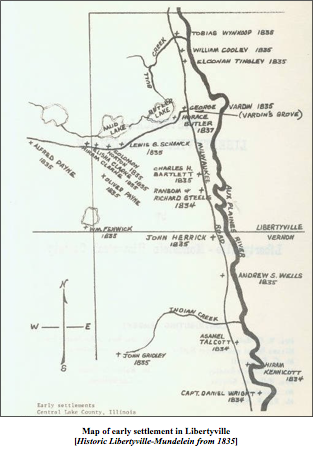

The Village of Libertyville can trace its origins back to the early 1830s, with the arrival of Englishman George Vardin. Vardin built a small cabin on the land between the Des Plaines River and Butler Lake, near the present-day location of the Ansel Cook House (now Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society). Although George Vardin and his had moved on from the area by 1835, others quickly settled in what was then known as “Vardin’s Grove,” including William Cooley, Elconah Tingley, Dr. William Crane, who opened the community’s first inn, Dr. J. H. Foster, its first practicing physician, Horace Butler, an attorney, and the Reverend Samuel Hurlburt[1]. In June of 1836, a stage coach line was established along the Milwauky Trace (an early Indian trading route) connecting Chicago to Milwaukee. The newly-established Milwaukee Road cut through the fledgling community at Vardin’s Grove, and helped to secure its future as an established town. A month later, on July 4th, 1836, the early settlers of Vardin’s Grove erected a flag pole in a small clearing, and dubbed the community Independence Grove. That autumn, the first school house was erected north of the clearing, near the current intersection of Milwaukee and Cook Avenues.[2]

In 1837, the citizens of Independence Grove applied to the state for a post office to service their community. It was then discovered that another town in Illinois already claimed the name Independence Grove. Early resident Archimedes Wynkoop suggested calling the town Libertyville, and the new name was adopted. When Libertyville was chosen as the seat of the newly-formed Lake County in 1839, the town’s name was changed again to Burlington, but reverted back to Libertyville when the county seat was given to Waukegan two years later.[3]

Development in Libertyville from 1840 to 1880 was slow but steady. During these decades, Lake County remained essentially a county of rural farming communities, and Libertyville was no exception. Census data indicates that the estimated population of Libertyville grew from around 67 residents in 1840 to 221 in 1880.[4] Other local histories give higher population numbers for this period—in his 1854 history of Lake County, Elijah M. Haines states that, at the time of his writing, the village “contains at the present time some three or four hundred inhabitants—two or three stores, a large commodious Hotel, a steam flouring mill and saw mill, and above all, two fine churches. . .”[5]

A directory of Libertyville Township published in The Past and Present of Lake County in 1878 gives a glimpse into the population of Libertyville at the end of this first period of development, before the town was linked to larger commercial centers through rail. The vast majority of those listed under the Libertyville P. O. box are farmers. Many—including Charles F. Albright, Ralph Bulkley (Section 9), Phillip Davis (Section 18), Joseph Davis (Section 6), Thomas Ellis (Sections 21 and 22), George Lawrence (Section 17), Colonel E. B. Messer (Section 21), James P. Norton (Section 19), William Price (Section 21), and John S. Wheeler (Sections 26 and 29), among others—owned substantial tracts within the township but outside of the town limits. Among those men listed in the directory who were not farmers were George Schanck, a seller of hardware and farming implements and a native of Libertyville; Marcian H. Seavey, a merchant; James Triggs, a harness maker; and William C. Triggs, a shoemaker.[6]

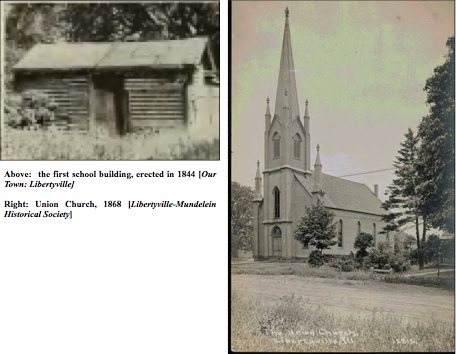

Early buildings in the town included the county’s first school building, erected in late 1836 near the current intersection of Milwaukee and Cook Avenues, and the Methodist Church building, completed in 1844 at what is now the intersection of Church Street and Brainerd Avenue. [7] In 1868, the Union Church was constructed along the south side of West Church Street, for use by the town’s Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Baptists, and Universalist congregations and The Grove House Hotel on Milwaukee Avenue, which opened in 1840 and was operated by Davis Steel, and later by Abram B. Fisher.[8] The first industrial development in the town included a grist and saw mill near the southwest corner of Lake Street and Milwaukee Avenue, by Dr. William Crane and Horace Butler, as well as a brick yard opened by Elconah Tingley near Walnut Street, north of the present business district.[9] Among these early buildings that were originally located within the Downtown survey area, none are still standing today.

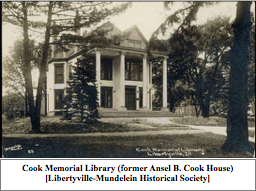

Residential development was also gradual and diffuse in this early period of Libertyville’s history. Within the Downtown survey area, very few houses dating from before 1880 survive. Unquestionably the most significant residential structure from this era, and a visual anchor of the village, is the home built for Ansel Brainerd Cook in 1878. Born in Haddam, Connecticut in 1823, Cook settled in Lake County in 1846, where he farmed nearly 450 acres near Libertyville. In 1849, Cook married Helen Maria Foster, the daughter of Libertyville physician Dr. Jesse H. Foster, and the couple relocated to Waukegan for four years. In 1853, A. B. Cook moved to Chicago, where he became a contractor and mason. He was best-known for laying the first flagstone in the city, and also held the masonry contract for the Chicago Water Tower on North Michigan Avenue. Cook was elected to the Illinois State Legislature in 1863, where he served two consecutive terms. Upon his return to Lake County in 1869, Cook was again elected to the State Legislature for a third time. After the Chicago Fire of 1871, Cook returned to Chicago and continued as a successful builder and stone contractor, and served as Alderman of the city’s 11th ward and President of the Chicago City Council.[10]

Ansel Cook purchased a large tract of land in Libertyville west of Milwaukee Avenue from his father-in-law in 1870. Work on the house and surrounding gardens began soon after, and was completed in 1878. The design of the house is attributed to Chicago architect William W. Boyington, whom Cook had worked with on the Chicago Water Tower years before.[11]

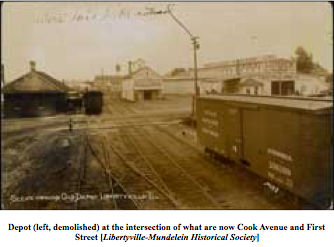

Although the introduction of the stage coach along Milwaukee Avenue in the 1830s had helped to attract some development to Libertyville, its citizens quickly realized that in order for the town to grow further, it would need to be linked to larger markets by a rail line. An early attempt by town officials to bring the railroad through Libertyville had failed in the 1850s, and the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway built a rail line connecting Milwaukee and Chicago in 1872 that bypassed Libertyville, going through nearby Rondout (then called Sulphur Glen) instead. In 1878, George H. Schanck, Dr. Sam Galloway and Col. E. B. Messner persuaded officials of that railroad company to run a spur from Rondout to Libertyville. In return, the village agreed to pay for the land, depot, bridge, across the Des Plaines river, and all materials for the line. General Walter Newberry, a local real estate developer, raised funds for the spur, which opened to much fanfare in May of 1880.[12] The original depot, which is no longer extant, was located along at the end of Sprague Street (now East Cook Street) at First Street.

Although the introduction of the stage coach along Milwaukee Avenue in the 1830s had helped to attract some development to Libertyville, its citizens quickly realized that in order for the town to grow further, it would need to be linked to larger markets by a rail line. An early attempt by town officials to bring the railroad through Libertyville had failed in the 1850s, and the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway built a rail line connecting Milwaukee and Chicago in 1872 that bypassed Libertyville, going through nearby Rondout (then called Sulphur Glen) instead. In 1878, George H. Schanck, Dr. Sam Galloway and Col. E. B. Messner persuaded officials of that railroad company to run a spur from Rondout to Libertyville. In return, the village agreed to pay for the land, depot, bridge, across the Des Plaines river, and all materials for the line. General Walter Newberry, a local real estate developer, raised funds for the spur, which opened to much fanfare in May of 1880.[12] The original depot, which is no longer extant, was located along at the end of Sprague Street (now East Cook Street) at First Street.

As expected, the coming of the railroad to Libertyville ushered in the town’s first building boom. Although only a single passenger train passed through the town daily, freight service along the line allowed for farmers surrounding the village to more easily transport their products to urban markets. This increased traffic into Libertyville led to the establishment of new businesses and increased residential population. According to an article on the history of transportation in Libertyville written by C. E. Carroll for the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society the years between 1880 and 1882 “saw the building of two grain elevators, a hotel and livery stable, two lumber yards, some half dozen store buildings, two churches, and about twenty-five new homes.”[13]

Encouraged by the increased development, local leaders petitioned Judge Francis E. Clark in Waukegan for the right to hold a referendum on incorporation. The referendum was held on April of 1882, a strong majority of Libertyville’s citizens voted to incorporate as a village. The first officers were elected a month later, and John Locke, a New-Hampshire-born farmer with holdings south of the village, was elected as Libertyville’s first mayor.[14]

Around the same time, local landowners with property close to the emerging business district began subdividing tracts for residential development. Josiah Butler subdivided a part of his farm west of Milwaukee Avenue around what is now Maple Avenue, George Schanck subdivided his holdings east of Milwaukee, creating Sprague Street (now Cook Avenue) to the new depot and building a mill and grain elevator along the new street. Caleb Wright opened Orchard Street (now Church Street) east of Milwaukee. Dr. Galloway and General Newberry also created new subdivisions north of the new rail spur. Within the Downtown survey area, nine houses built in the decade after the establishment of the railroad in Libertyville survive, including several houses along the newly-opened Maple Avenue, Park Avenue, and Brainerd Avenue.[15]

Around the same time, local landowners with property close to the emerging business district began subdividing tracts for residential development. Josiah Butler subdivided a part of his farm west of Milwaukee Avenue around what is now Maple Avenue, George Schanck subdivided his holdings east of Milwaukee, creating Sprague Street (now Cook Avenue) to the new depot and building a mill and grain elevator along the new street. Caleb Wright opened Orchard Street (now Church Street) east of Milwaukee. Dr. Galloway and General Newberry also created new subdivisions north of the new rail spur. Within the Downtown survey area, nine houses built in the decade after the establishment of the railroad in Libertyville survive, including several houses along the newly-opened Maple Avenue, Park Avenue, and Brainerd Avenue.[15]

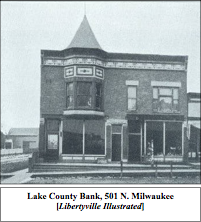

Commercial development continued at an increased pace through the 1890s. The Libertyville Hotel opened in a new brick building at the southwest corner of Milwaukee Avenue and Church Street in the mid-1890s. The establishment was run by James Furney and E. C. Tillotson, who had experience working in a hotel in Deerfield.[16] Other commercial structures built during second half of the decade include the H. B. Eger Hardware Building at 508 N. Milwaukee and a brick two-part commercial block at 116-118 E. Cook Avenue. The Lake County Bank, the first bank in the village, was established in 1892, and occupied a brick building at 525 N. Milwaukee Avenue before moving to the northwest corner of Cook and Milwaukee Avenues in 1894.[17]

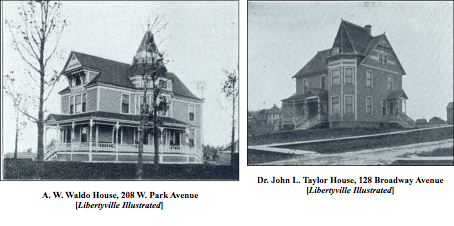

The 1890s also saw the construction of many impressive houses built on newly-subdivided lots surrounding downtown, including several that are still standing within the survey area. The house at 208 W. Park Avenue was built in 1896 for A. W. Waldo, a native of Vermont who retired from his business in Chicago and settled in Libertyville. Dr. John L. Taylor, a respected local physician who served as Lake County coroner for over 40 years, built a handsome Queen Anne residence at 128 Broadway Avenue in 1893. Franklin P. Dymond’s house at 130 W. Maple Street was built around 1890. Dymond served as president of Lake County Bank at the turn of the 20th century, and was a partner in the Lake County Gravel Company.

The 1890s also saw the construction of many impressive houses built on newly-subdivided lots surrounding downtown, including several that are still standing within the survey area. The house at 208 W. Park Avenue was built in 1896 for A. W. Waldo, a native of Vermont who retired from his business in Chicago and settled in Libertyville. Dr. John L. Taylor, a respected local physician who served as Lake County coroner for over 40 years, built a handsome Queen Anne residence at 128 Broadway Avenue in 1893. Franklin P. Dymond’s house at 130 W. Maple Street was built around 1890. Dymond served as president of Lake County Bank at the turn of the 20th century, and was a partner in the Lake County Gravel Company.

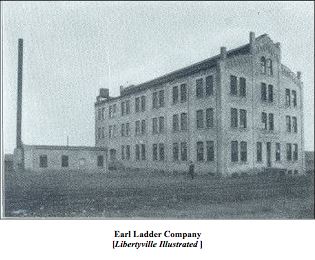

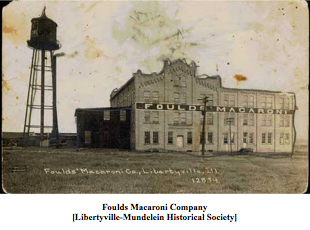

The presence of the railroad continued to encourage industrial development along the spur east of Milwaukee Avenue. Several buildings were erected by local speculators in the 1890s to attract manufacturers to the area, and by the end of the decade there was a proliferation of small industries on Sprague (Cook) and Orchard (Church) Avenues, including the F. E. Hanley & Company factory, which produced butter and cheese; Wright & Sons lumber yard; the Chicago Metal Stamping Company, begun by Fred Bischoff; and several other structures, including an agricultural implements manufacturer, ice house, and stock yard.[18] In 1898, the Earl Ladder Company moved from Michigan to Libertyville, occupying a three-story brick building on the north side of what is now Church Street east of the downtown core. The building later housed the Foulds Macaroni Company.[19]

The presence of the railroad continued to encourage industrial development along the spur east of Milwaukee Avenue. Several buildings were erected by local speculators in the 1890s to attract manufacturers to the area, and by the end of the decade there was a proliferation of small industries on Sprague (Cook) and Orchard (Church) Avenues, including the F. E. Hanley & Company factory, which produced butter and cheese; Wright & Sons lumber yard; the Chicago Metal Stamping Company, begun by Fred Bischoff; and several other structures, including an agricultural implements manufacturer, ice house, and stock yard.[18] In 1898, the Earl Ladder Company moved from Michigan to Libertyville, occupying a three-story brick building on the north side of what is now Church Street east of the downtown core. The building later housed the Foulds Macaroni Company.[19]

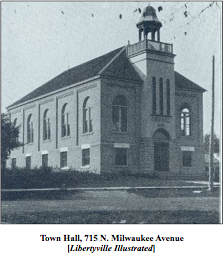

Through this late-19th-century boom, the village of Libertyville also established new structures and spaces that supported the civic and social lives of its residents. In 1893, a section of C. Frank Wright’s new residential subdivision east of Milwaukee Avenue and north of Park Avenue was set aside for a park. The park, named Central Park, provided a much-needed public open space for the community. Libertyville’s first town hall was built on the east side of Milwaukee Avenue north of Lake Avenue in 1894. The imposing brick building was designed by Chicago architect William Boyington, who also designed Ansel Cook’s mansion in 1878. The Lake County Independent reported in May of 1894 that “the ceiling, tower, cornices, hip moulds, and cresting are to be of imported German sheet steel which will be furnished, stamped and put on by our home factory Fred F. Bischoff & Co.”[20] More practical improvements also came to Libertyville in the final decades of the 19th century, including the installation of wooden sidewalks and street lamps along Milwaukee Avenue and the opening of the village’s first electric light plant in 1896.[21]

Through this late-19th-century boom, the village of Libertyville also established new structures and spaces that supported the civic and social lives of its residents. In 1893, a section of C. Frank Wright’s new residential subdivision east of Milwaukee Avenue and north of Park Avenue was set aside for a park. The park, named Central Park, provided a much-needed public open space for the community. Libertyville’s first town hall was built on the east side of Milwaukee Avenue north of Lake Avenue in 1894. The imposing brick building was designed by Chicago architect William Boyington, who also designed Ansel Cook’s mansion in 1878. The Lake County Independent reported in May of 1894 that “the ceiling, tower, cornices, hip moulds, and cresting are to be of imported German sheet steel which will be furnished, stamped and put on by our home factory Fred F. Bischoff & Co.”[20] More practical improvements also came to Libertyville in the final decades of the 19th century, including the installation of wooden sidewalks and street lamps along Milwaukee Avenue and the opening of the village’s first electric light plant in 1896.[21]

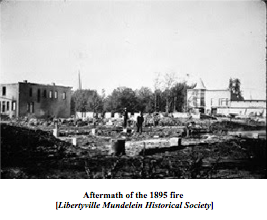

Fire of 1895

In August of 1895, a devastating fire swept through Libertyville’s business district, destroying 27 buildings between Sprague (now Cook) Avenue and School Street on the east side of Milwaukee Avenue. With no fire department and only private wells in the village, there was little that its citizens could do to stop the fire. As a last ditch effort to halt the spread of the flames, the Grove Hotel was dynamited, although by that point the fire had begun to die out. The Lake County Independent stated in an article on the catastrophe the following day that the fire had been almost inevitable:

In August of 1895, a devastating fire swept through Libertyville’s business district, destroying 27 buildings between Sprague (now Cook) Avenue and School Street on the east side of Milwaukee Avenue. With no fire department and only private wells in the village, there was little that its citizens could do to stop the fire. As a last ditch effort to halt the spread of the flames, the Grove Hotel was dynamited, although by that point the fire had begun to die out. The Lake County Independent stated in an article on the catastrophe the following day that the fire had been almost inevitable:

Time and time again have the people been warned that the worst would come, but resting in a false security no provision was made for time of need, and almost the entire business section of the city fell as easy prey to the fire’s rapacity. Had it not been for the recent heavy rains and the absence of a strong wind, Libertyville today would be hardly more than a remembrance—a mass of blackened, smoking embers.[22]

Two days after the fire, the village board passed an ordinance requiring that any new building constructed in the downtown be of brick. Sanborn Fire Insurance Company maps show that the fire limits stretched from just north of Broadway to Lake Street on either side of Milwaukee Avenue. Rebuilding occurred quickly—the 1897 Sanborn map shows several new buildings already occupying the burned district along the east side of Milwaukee. Among these new buildings were the Schanck Building and the Triggs & Taylor Building, both of which are still standing within the survey area. Triggs & Taylor was an early grocery store in Libertyville, opened by John Eli Triggs and C. W. Taylor in 1892. Initially, the company occupied a frame building on the east side of Milwaukee Avenue. After the building was destroyed by fire, Triggs and Taylor immediately began to rebuild, erecting a handsome brick commercial block with Queen-Anne metal bays and cornice. [23] George Schanck, who had established his hardware business at the northeast corner of Milwaukee and Cook Avenues over twenty years earlier, also rebuilt his business soon after the fire, erecting a two-story brick commercial block that, though altered, still stands today.[24]

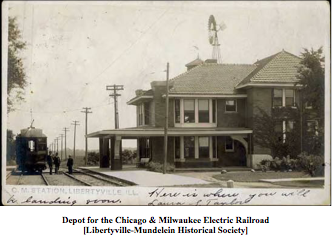

While the population and building boom of the late 19th century in Libertyville established the village as a commercial and industrial center within a rural farming community, the early decades of the 20th century witnessed its evolution into a suburban hub for many of the country estates owned by prominent Chicagoans that proliferated throughout Lake County during this period. This movement began with the construction of the Madison spur of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway opened at the north end of the village in 1900. The spur allowed for regular commuter service to the village for the first time, encouraging city dwellers to settle in and around town.[25] Access was further improved when the Chicago & Milwaukee Electric Railroad built a spur from Lake Bluff to Libertyville in 1903. The electric line ran at the southern end of the village, crossing east to west south of Park Avenue. Other improvements to the village’s infrastructure also occurred during the first decade of the 20th century, including the creation of a local franchise of the North Shore Gas Company in 1904, and the establishment of water and sewer systems around the same time.[26]

Residential Development: 1900-1920

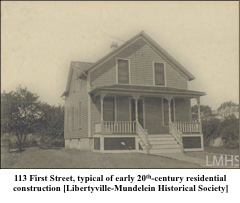

In the first ten years of the 20th century, the population of Libertyville doubled, from 846 residents to 1,724. Residential building within the Downtown survey area reflects this spike—between 1900 and 1910, over forty houses were erected, many along Frist Street, Maple Avenue, Park Avenue, and Stewart Avenue. Although the rate of growth slowed between 1910 and 1919—the village population increased by 402 residents—building remained relatively robust, with an additional 21 homes built during that decade.

Commercial Development: 1900-1920

Commercial development within the Village of Libertyville also expanded rapidly in the first 20 years of the century. From 1900 to 1910 eleven buildings were constructed within the central business district—nine along Milwaukee Avenue and two on Cook Avenue. An additional three buildings were erected between 1910 and 1920.

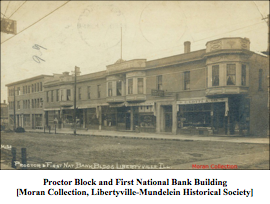

The most important commercial building erected during the first decade of the century was the Proctor Block. The building was financed by brothers Robert, Charles, and Richard Proctor and their cousin Elisha, and designed by Chicago architect William Krieg. The two-story brick building housed commercial storefronts on the first story, while much of the second floor was taken up by rooms for the Castle Hotel, the largest of three operating hotels in Libertyville at the time. When it was completed in 1903, the block was lauded as “Libertyville’s first metropolitan building, the pride of all citizens. . . Towns five times the size of Libertyville cannot boast of buildings similar to the Proctor Block – and it can be said that such a building as the Proctor Block is just the kind of building Libertyville requires. . .”[27]

The most important commercial building erected during the first decade of the century was the Proctor Block. The building was financed by brothers Robert, Charles, and Richard Proctor and their cousin Elisha, and designed by Chicago architect William Krieg. The two-story brick building housed commercial storefronts on the first story, while much of the second floor was taken up by rooms for the Castle Hotel, the largest of three operating hotels in Libertyville at the time. When it was completed in 1903, the block was lauded as “Libertyville’s first metropolitan building, the pride of all citizens. . . Towns five times the size of Libertyville cannot boast of buildings similar to the Proctor Block – and it can be said that such a building as the Proctor Block is just the kind of building Libertyville requires. . .”[27]

North of the Proctor Block, the First National Bank Building replaced the Methodist Church Building at the southeast corner of Milwaukee Avenue and School Street in 1913. The bank had been organized in 1903, and was purchased by the Gridley family in 1906.[28] In 1912, the Methodist Church began construction on a new brick church building on Brainerd Avenue to accommodate its growing congregation. John L. Taylor purchased the property and transferred it to the Gridley family who tore the frame church down and built a new, three-story brick building on the lot. The bank remained on the first floor of the building until it merged with Lake County National Bank in 1932.[29]

Other substantial commercial buildings constructed during this period include the two-story brick block with Queen Anne bays at 533-541 N. Milwaukee Avenue (built c. 1900), and the two-story brick block at 602-610 (built c. 1905).

Although no longer standing, Libertyville’s first auto garage opened near the northwest corner of Milwaukee Avenue and Lake Avenue around 1912, indicating that the age of the automobile had come to the village. Sanborn maps show the two-story garage building, and an advertisement for Libertyville Garage appears in the 1913 telephone directory for Lake County that includes Libertyville.[30] In 1914, John Bernard opened a Chevrolet dealership in the building.[31]

Industrial Development: 1900-1920

The first decades of the 20th century also saw the arrival of more substantial industrial development within the village. Among the largest companies to open in Libertyville in this period was the American Wire Fence Company. The company opened in the village in 1905, and by 1912 employed over 60 people. The company ceased operations in the late 1930s.[32]

The W. C. Holt Manufacturing Company, founded in Chicago, moved to a new factory on Fifth Avenue east of downtown Libertyville in 1901. The company manufactured tanning pelts used for wood dusters, carriage robes, rugs, and boas. The company remained in business for a relatively short period, ceasing operation sometime between 1908 and 1912.[33]

The W. C. Holt Manufacturing Company, founded in Chicago, moved to a new factory on Fifth Avenue east of downtown Libertyville in 1901. The company manufactured tanning pelts used for wood dusters, carriage robes, rugs, and boas. The company remained in business for a relatively short period, ceasing operation sometime between 1908 and 1912.[33]

Of the factories operating just after the turn of the century, only one was located in the Downtown survey area—the Foulds Macaroni Company. Founded in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1898, the company moved to Libertyville in 1905, occupying the factory building that previously housed the Earl Ladder Company on East Church Street. The business, now closed, operated in the building for over 100 years, and was a major employer in the village for decades. The company was also known for its involvement in the community, inviting all its residents to summer picnics and Christmas parties.”[34]

West of Milwaukee Avenue, and just northwest of the Downtown survey area, was Yore Brothers Milk & Cream Bottling Company. Founded in 1905, Yore Brothers processed and shipped milk from over forty surrounding dairy farms, bottling around 1500 gallons of milk per day. The plant closed in the mid-1920s, and the building burned in 1931.[35]

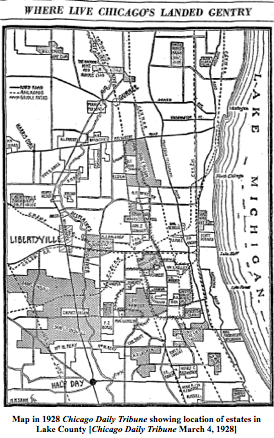

Samuel Insull and the Rise of the Country Estate

With improved transportation into Chicago, many of the city’s wealthy businessmen began to purchase farms throughout Lake County for use as country estates in the early 20th century, including the rural parcels surrounding the Village of Libertyville. In his 1912 History of Lake County Illinois, C. Chamberlain Tracey wrote of the phenomenon as “the substitution for the suburban home of wealth of the wealth of the country estate of the great entrepreneur, who was ready to apply even to his rest and recreation place the methods of business.”[36] Well-known Chicago luminaries like J. Ogden Armour,J. H. Hiland, J. Medill Patterson, John R. Thompson, David Adler, and Ernest Hecht all established estates near the village.[37]

Of this new class of ‘landed gentry,’ none had a greater impact on the development of the Village of Libertyville than Samuel Insull. The public utilities magnate and former partner of Thomas Edison purchased the 160-acre Barr farm south of the village limits in 1906, and moved with his family into the existing farm house on the property the next year. Over the next 20 years, Insull extended his holdings around the original farm, ultimately acquiring 6,000 acres. In 1914, Insull commissioned architect Benjamin Marshall to design a Renaissance-Revival mansion to replace the original farm house.[38]

Initially, Insull intended to supply his estate with electricity by extending a transmission line to Libertyville’s electric plant. But, after observing the scattered and limited electrical service available to much of Lake County, Insull concocted an audacious plan to connect all the towns and farms in the area under a single electrical network. He purchased the existing ten part-time electrical plants (including the one in Libertyville) and “set out to build a transmission-line network to connect twenty of the twenty-two towns and about 125 of the farms in the area.[39] The system was a complete success, and provided the blueprint for systemized rural electrification for the entire country.

After the success of the Lake County venture, Insull extended his reach into the suburban and rural areas all around Chicago—in 1911, he merged a number of different electric companies from this area into a new corporation, the Public Service Company of Northern Illinois.[40]

Insull’s investments in the village went far beyond just the establishment of full-time electrical service. In 1916, he purchased the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee Electric Railroad line, which ran between his property and the village. In 1928, he donated land and money for the construction of the Elizabeth Condell Hospital. Insull also owned and operated the Libertyville Trust and Savings Bank in town.[41]

Insull’s investments in the village went far beyond just the establishment of full-time electrical service. In 1916, he purchased the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee Electric Railroad line, which ran between his property and the village. In 1928, he donated land and money for the construction of the Elizabeth Condell Hospital. Insull also owned and operated the Libertyville Trust and Savings Bank in town.[41]

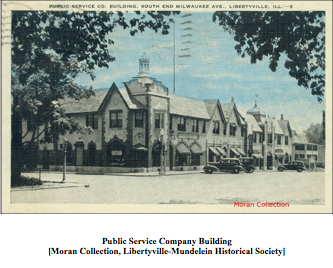

Within the Downtown survey area, Insull’s legacy is most clearly represented by the Public Service Company Building at 340-354 N. Milwaukee Avenue. Built in 1928 at a cost of over $250,000, the building housed the utility company’s headquarters, as well as the Libertyville Trust & Savings Bank. Additional retail spaces occupied the ground floor of the building, and the second floor contained office space, as well as seven kitchenette apartments. According to an article in the November 17, 1928 edition of the Lake County Register, the Public Service Company’s space showcased “the very latest improvements for display of merchandise and convenience to patrons. . . . A feature of the store equipment will be a miniature model all electric kitchen where the housewife can see the various electrical appliances in actual use.”[42]

Libertyville in the 1920s

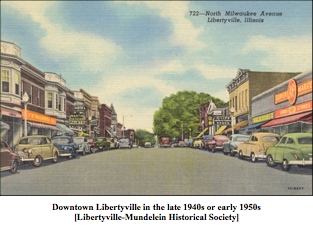

The decade of the 1920s was a time of explosive growth in urban and suburban centers across the country. Libertyville also saw its share of commercial and residential development during this decade, although at a less impressive rate than that seen in the first 20 years of the century. From 1920 to 1930, the population of the village increased from 2,126 residents to 2,791. Farm land around the perimeter of the village center was opened for development, and numerous subdivisions were platted during this time, including Libertyville Highland, Copeland Manor North, Copeland Manor South, and Thornbury Village. Increased traffic on the North Shore Electric Line led the construction of an additional line through the village in 1926. Many streets were paved throughout the village for the first time, and parking lines were drawn downtown.

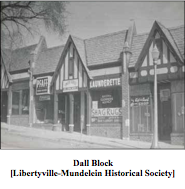

Within the Downtown survey area, nine commercial buildings were constructed during the decade. Samuel Insull’s Public Service Building graced the south end of the business district in 1928. In 1925, Benjamin L. Dall constructed a new one-story commercial block at the northwest corner of Milwaukee Avenue and Lake Street. The new building, which contained eleven small storefronts, replaced the Eli P. Penniman house, which was built around 1850. South of the Dall Building, on the west side of Milwaukee Street, the First Lake County National Bank was completed in 1923.[43]

Among the most important institutional additions to the village during this period was the conversion of the Ansel B. Cook Mansion and grounds into a public library and park. Cook had left the house to his widow Emily Barrows Cook, with the understanding that it be deeded to the Village of Libertyville upon her death. Emily Barrows died in 1919, and the property passed to the village in 1920. The following year, the new library opened in the house. The first library in the village had started by the Alpha Club in 1909 and housed in the Decker and Bonds drug store—the library later moved to the Village hall before moving to the Cook Mansion.[44]

Among the most important institutional additions to the village during this period was the conversion of the Ansel B. Cook Mansion and grounds into a public library and park. Cook had left the house to his widow Emily Barrows Cook, with the understanding that it be deeded to the Village of Libertyville upon her death. Emily Barrows died in 1919, and the property passed to the village in 1920. The following year, the new library opened in the house. The first library in the village had started by the Alpha Club in 1909 and housed in the Decker and Bonds drug store—the library later moved to the Village hall before moving to the Cook Mansion.[44]

Residential construction in the survey area continued to build on earlier development in the 1920s. Many of the houses built during this period were modest Bungalows and Craftsman designs.

Growth slows in the 1930s and early 1940s

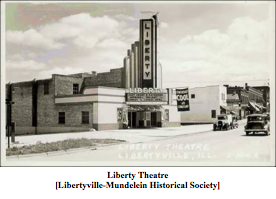

As the country slid deeper into the Great Depression through the 1930s, residential and commercial development in Libertyville slowed considerably. Between 1930 and 1940, the population grew by just 139 residents. Within the Downtown survey area, only three single-family homes were constructed. Commercial development fared slightly better, with six new buildings erected downtown between 1930 and 1939. Among the most significant of these was the Liberty Theater, which opened to great fanfare in Libertyville in August of 1937. Owner Fred W. Dobe had first polled residents in the village to determine if a new movie theater was warranted—at the time, the La Villa movie theater was in operation on the second floor of the First National Bank Building. Designed by Chicago architect E. P. Rupert, the freestanding theater building boasted a 750-seat capacity, air conditioning, and other modern amenities.[45] Although extensively altered, the theatre building still stands at the north end of the central business district.

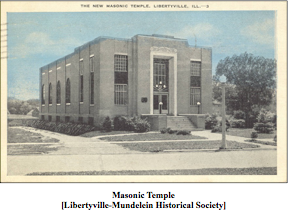

Other notable buildings from this period include the Post Office Building, constructed in 1935 along West Church Street, and the Libertyville Masonic Temple, a striking Art Deco design erected at 356 Brainerd Avenue. Although work on the building had begun in the 1920s, it was not completed until the early 1930s.

Other notable buildings from this period include the Post Office Building, constructed in 1935 along West Church Street, and the Libertyville Masonic Temple, a striking Art Deco design erected at 356 Brainerd Avenue. Although work on the building had begun in the 1920s, it was not completed until the early 1930s.

The 1930s saw the movement of national chain stores into Libertyville’s central business district. Some of these chain stores opened within existing buildings along Milwaukee Avenue. F. W. Woolworth’s, among the most well-known five-and-dime stores in America, opened a branch in the Proctor building in the early 1930s. The store underwent a renovation and extension in 1940—with 5,000 square feet of retail space, it became the largest shop in the village.[46] Others were placed in purpose-built structures. In 1931, a one-story building was erected at 515 N. Milwaukee Avenue for the Consumer’s Sanitary & Coffee Company, a grocery chain later bought by Kroger. [47] The Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, which had already established itself in the village several years earlier, moved into a new one-story commercial structure at 525-331 N. Milwaukee Avenue in 1940. Langworthy’s Department Store occupied the south half of the building, while the A & P was located in the north half.[48]

LIBERTYVILLE IN THE POST-WORLD WAR II ERA

Sharply contrasting with the protracted developmental lull of the 1930s and early 1940s, the decades following the end of World War II were a time of unprecedented growth throughout the United States, eclipsing even the boom of the 1920s. This was especially true in suburban areas, helped along by an ever-expanding and improving system of roads, including new interstate highways, and the increased availability of financing for single family homes. Libertyville was not immune to this explosion of growth, although much of the new residential, industrial, and commercial development occurred outside of the Downtown survey area. The village population grew from 3,930 residents in 1940 to 5,426 in 1950, and reached 8,560 by 1960—an increase of over 200% in just two decades. Articles in local newspapers from the late 1950s and early 1960s regularly articulated an ever-growing list of speculative housing projects, some in existing subdivisions, others in new tracts set ever-farther from the village center. An article in August 1, 1957 edition of the Independent Register reported that over 1,100 new houses were slated for construction within the next year. A subsequent article in 1963 outlined an additional 1,000 houses planned for construction that year.[49]

Residential development within the Downtown survey area during the post-war period was relatively limited, given that the area had reached residential maturity some time before. Twelve single-family home were constructed in the survey area between 1950 and 1959, and a number of multi-family residential buildings were built in the 1960s. Most of the 1950s houses were simple Ranch, Minimal Traditional, or Contemporary designs, and are scattered throughout the district.

Industrial expansion also marked the post-war period in Libertyville, with a growing number of companies were drawn to the area. Several companies—including the Morton Manufacturing Company, the Onsrud Cutter Manufacturing Company, and the Brown Paper Goods Company—moved into existing factory buildings within Libertyville’s original industrial district just east of downtown.[50] Others were located farther from the village center. A brochure on Libertyville published by the Chamber of Commerce in the early 1960s lists 20 manufacturing firms located within the village—by the mid-1970s, that number had grown to over 50.[51]

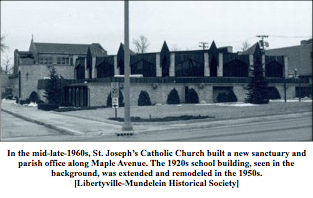

Institutional, educational, and religious buildings were also expanded or added during the post-war period to keep up with the growing population of the village. St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, whose congregation had grown to over 1,000 families by 1960, extended its original 1920s school building on East Maple Avenue with a substantial addition in the mid-1950s. In 1966, the congregation replaced its 1905 church building (which could only accommodate 300 people) for a sprawling Neo-Expressionist sanctuary building at the southeast corner of Milwaukee and Maple Avenues. A new church office was added to the complex a few years later.[52] The Methodist Church also razed its 1913 building on Brainerd Avenue in 1967 and built a larger, modern sanctuary and educational building. In 1968, a new public library building was constructed just east of the Cook Mansion, which was later turned over to the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society. Condell Memorial Hospital, located outside of the survey area, was also expanded, with the Noble Wing built in 1952, and the Hough Maternity Wing completed in 1954.[53]

Institutional, educational, and religious buildings were also expanded or added during the post-war period to keep up with the growing population of the village. St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, whose congregation had grown to over 1,000 families by 1960, extended its original 1920s school building on East Maple Avenue with a substantial addition in the mid-1950s. In 1966, the congregation replaced its 1905 church building (which could only accommodate 300 people) for a sprawling Neo-Expressionist sanctuary building at the southeast corner of Milwaukee and Maple Avenues. A new church office was added to the complex a few years later.[52] The Methodist Church also razed its 1913 building on Brainerd Avenue in 1967 and built a larger, modern sanctuary and educational building. In 1968, a new public library building was constructed just east of the Cook Mansion, which was later turned over to the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society. Condell Memorial Hospital, located outside of the survey area, was also expanded, with the Noble Wing built in 1952, and the Hough Maternity Wing completed in 1954.[53]

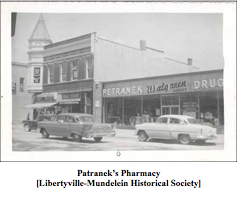

Thirteen new commercial buildings were built within the Downtown area in the 1950s, including Petranek’s Pharmacy, which rebuilt at its original location (426 N. Milwaukee Avenue) after a fire in 1954. An additional eight were built in the 1960s—among the more striking designs from this period was Joseph’s Flower Shop, a Neo-Expressionist design erected at 200 E. Church Street in 1962.

Thirteen new commercial buildings were built within the Downtown area in the 1950s, including Petranek’s Pharmacy, which rebuilt at its original location (426 N. Milwaukee Avenue) after a fire in 1954. An additional eight were built in the 1960s—among the more striking designs from this period was Joseph’s Flower Shop, a Neo-Expressionist design erected at 200 E. Church Street in 1962.

The Fall and Rise of Libertyville’s Downtown

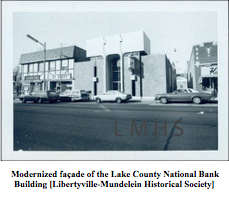

As early as the late 1950s, concern was expressed among Libertyville’s leaders about the long-term viability of the village’s central business district, as shopping centers located in less densely-populated areas around small towns throughout the state began to drain revenue away from historic downtowns. Efforts were made in the late 1950s and 1960s by the village to make the downtown more inviting to shoppers—Milwaukee Avenue was widened in 1960, and land was purchased within the district for parking lots. New sidewalks and lighting were installed. Also during this period, many business owners began to modernize the storefronts and facades of older buildings—many historic facades were obscured with aluminum slip covers in order to make them more fashionable and appealing to potential shoppers. Despite these changes, Libertyville’s historic downtown continued to lose ground to new shopping centers, with their modern décor, spacious layouts, and ample parking. A sprawling new strip mall built the northeast corner of Milwaukee and Park Avenues in the 1950s, signaled the beginning of a spate of new commercial development south of Libertyville in the following two decades, including Hawthorn Mall and New Century Town.[54]

By the early 1980s, the situation had only grown direr. In a two-part report on the future of Downtown Libertyville published in the Libertyville Review in April of 1983, Don McCammon stated baldly the difficulty in competing with new shopping centers outside of the village center:

Less than five minutes south of downtown is Cambridge Plaza. . .Another two minutes further south is Libertyville’s newest shopping mall, Red Top Plaza. . . Ten minutes south of downtown, Libertyville shoppers need to park only once to visit the 100-plus stores, including three major department stores, in Hawthorn Center. Hawthorn offers indoor shopping, specialty shops, and several restaurants.[55]

Less than five minutes south of downtown is Cambridge Plaza. . .Another two minutes further south is Libertyville’s newest shopping mall, Red Top Plaza. . . Ten minutes south of downtown, Libertyville shoppers need to park only once to visit the 100-plus stores, including three major department stores, in Hawthorn Center. Hawthorn offers indoor shopping, specialty shops, and several restaurants.[55]

The establishment of Libertyville’s Main Street program in the late 1980s signaled the beginning of the downtown’s renaissance. Through the unflagging efforts of residents, government officials, and business leaders, by the late 1990s Libertyville’s historic downtown core was once again the thriving center of the community. The revitalization of downtown has led to renewed interest in residential properties close to the village center, with mixed consequences for its historic homes. Although new residential construction within the Downtown survey area remained low in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, the number of new homes built in the area increased dramatically in the 2000s and 2010s. The majority of these residences were constructed as part of the School Street development, completed in 2015. Other houses built in the survey area during this period were scattered, and lots previously occupied by older homes.

[1]Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, published by the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, 1971, p. 6.

[2]Ibid, p. 7; Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, Libertyville, Illustrated, Marceline, Mo. : Walsworth Pub. Co.; Libertyville, Ill. : Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, 1993, p. 4.

[3] Jim Moran, Libertyville (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2006), p. 7.

[4] “Population Estimates and Census Counts: Libertyville and Mundelein, Illinois” unpublished paper located in Historical Demographics folder, local history collection, Cook Memorial Public Library.

[5] Elijah M. Haines, Historical and Statistical Sketches of Lake County, State of Illinois: in Two Parts, the First Consisting of General Observations, the Second Gives a Minute Review of Each Township in its Order (Libertyville, IL: republished by the Illinois-Mundelein Historical Society, 1973, originally published 1852), p. 89.

[6] The Past and Present of Lake County, Illinois (Chicago: William LeBaron, 1877), p. 401-412.

[7] Laura Hickey, Arlene Lane, and Sonia Schoenfield, Then & Now: Libertyville (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2010), p. 31

[8] John J. Halsey and C. Chamberlain Tracey, A History of Lake County, Illinois (Philadelphia: R. S. Bates, 1912), p. 716; Moran, p. 12; The Past and Present of Lake County, 401-412.

[9] Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, p. 11.

[10] “The Ansel B. Cook House,” Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society website (http://www.lmhistory.org/cookhouse.html).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, p. 16-17; Craig L. Pfannkuche, “Libertyville,” Encyclopedia of Chicago website (http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/740.html).

[13] C. E. Carroll, “Transportation,” Essay published Cook Memorial Public Library website (http://www.cooklib.org/Localhistory/CarrollEssays/Essays/Transportation.html).

[14] Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, p. 22; Libertyville Illustrated, p. 7.

[15] C. E. Carroll , “The Booms” Essay published on Cook Memorial Public Library website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/348/Exhibit/2)

[16] Libertyville Illustrated, p. 27.

[17] “American National Bank of Libertyville,” in Banks and Banking Folder at Cook Memorial Library Local History Room.

[18] Sanborn Fire Insurance Company, Map of Libertyville, Illinois, 1897; Libertyville, Illustrated, p. 42.

[19] “Earl Ladder Co.” Undated pamphlet in collection of the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society and Cook Memorial Public Library. Accessed through the Illinois Digital Archives website (http://www.idaillinois.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/cookmemo11/id/6354/rec/6)

[20] “Our New Town House,” Lake County Independent, May 25, 1894 p. 5.

[21] Libertyville Illustrated, p. 29.

[22] “All is Ruin,” Lake County Independent, August 31, 1895, p. 1

[23] “John Eli Triggs, 85, Old Resident, Dies,” Lake County Independent, December 30, 1943 p. 1.

[24] Then & Now: Libertyville, p. 47.

[25] C. E. Carroll, “The Booms.”

[26] Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, p. 24

[27] National Register of Historic Places, Proctor Building, Libertyville, Lake County, Illinois, National Register #98000064, Section 8, p. 13.

[28] “Historical Timeline of Early Libertyville Banks,” included in Banks folder at Cook Memorial Public Library Local History Room.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Telephone Directory: January 1913 (Chicago: Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation, 1913).

[31] Moran, p. 59.

[32] “American Wire Fence Company,” part of “Made in Libertyville,” online exhibit at the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/330/Exhibit/3).

[33] “W. C. Holt Manufacturing Company,” part of “Made in Libertyville,” online exhibit at the Libertyville- Mundelein Historical Society website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/330/Exhibit/12).

[34] “Foulds Macaroni Company,” part of Made in Libertyville,” online exhibit at the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/330/Exhibit/7).

[35] “Yore Brothers Bottled Milk & Cream,” part of “Made in Libertyville,” online exhibit at the Libertyville- Mundelein Historical Society website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/330/Exhibit/13).

[36] History of Lake County, Illinois, p. 198.

[37] Business Philosopher, Volume 3, Part 2, p. 436-7.

[38] Forrest McDonald, Insull, the Rise and Fall of a Billionaire Utility Tycoon (Beard Books, 2004), p. 151.

[39] Ibid, p. 154.

[40] Ibid, p. 159.

[41] National Register Nomination, Public Service Building, Libertyville, Lake County, Illinois, National Register #83003581.

[42] Lake County Register, November 17, 1928, p. 2

[43] “Village Life,” from “Libertyville in the Twenties,” an online exhibit at the Cook Memorial Public Library District website (http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/292/Exhibit/4).

[44] Historic Libertyville-Mundelein from 1835, p. 25-6; “Library History,” Cook Memorial Public Library District website (http://www.cooklib.org/index.php/library-history).

[45] Then & Now: Libertyville, p. 38.

[46] Ibid, p. 44.

[47] “Start Work on New Consumer Building Here,” Independent Register, August 20, 1931.

[48] “Two Stores Hold Grand Opening Friday,” Independent Register, June 22, 1940, p. 1.

[49] “Libertyville Looks to Big Development,” Independent Register, September 26, 1963, p. 6T; “Plan 1,110 New Homes in Libertyville District,” Independent Register, August 1, 1957, p. 1

[50] “Morton Manufacturing Co.” from “Made in Libertyville,” online exhibit at Cook Memorial Public Library District website ( http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/330/Exhibit/9).

[51] Libertyville Chamber of Commerce, The Land of Libertyville: Where the City and the Country Meet (Libertyville: Libertyville Chamber of Commerce, 1963), p. 12; Libertyville Chamber of Commerce, Libertyville (Libertyville, Ill: McCoy Associates, 1972, p. 16.

[52] Then & Now: Libertyville, p. 32.

[53] Then & Now: Libertyville, p. 92) [54] Byrne, John B. Cuneo Museum and Gardens (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), p. 9. [55] Don McCammon, “Downtown Libertyville,” Libertyville Review, April 7, 1983, p. 18-19.

[54] Byrne, John B. Cuneo Museum and Gardens (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), p. 9.

[55] Don McCammon, “Downtown Libertyville,” Libertyville Review, April 7, 1983, p. 18-19.